Lighting 103: Greg Heisler on Light and Color

Abstract: Chromatically complex light adds much more realism to your lit photos.

Today’s Lighting 103 post features excerpts from a bar conversation with Greg Heisler. It's just as if we cornered him at a conference (which I did) and he agreed to have a drink and talk color (which he did).

This is roadmap stuff. It's above and beyond the specific info he includes with each of the assignments in his book, 50 Portraits, the companion text to L103.

__________

Here's the scene. It's a few minutes after midnight at an Embassy Suites near the airport in Columbus, Ohio. Greg and I grab a drink just as the bartender is closing her register in the lobby bar.

I have had a few of these types of conversations with Greg, for which I am grateful. He is always so generous with his knowledge and experience, as those of you who have read his book can attest.

We talked for a couple hours—an early exit by past standards at the Vista bar in Dubai. I was recording, with permission, so I could avoid spending the time scribbling. Below I have transcribed the half-dozen or so takeaway nuggets that I would have been wracking my brain to remember the next morning.

It's tough, because it's the side stories woven throughout, and not the nuggets, that you tend to remember. So we'll be sticking to the salient takeaways. And not, for instance, relaying the parable about the photographer who finds success shooting nothing but hairy rectums with a red gel.

(Moral: Your work will never make everyone happy. But if you're lucky, it'll make some people really happy.)

And for the record, that vignette would not even crack the Top Ten of photo-related stories that came out of late night talks at The Vista in Dubai. (And I'm pretty sure David Burnett holds positions one through five.)

For clarity, the text with inset borders (AKA blockquotes) is Greg talking.

Why are Color and Light so Important?

Light is its own environment. Just as we can drop a subject into a physical environment, the color and quality of the light is an environment unto itself. It can create an imaginary environment, with elements unseen in the frame yet obviously influencing the subject.

As Greg puts it:

Translation: the universal nature of light and color can make a photo instantly appear as organic and authentic. Or it can set off warning bells in your subconscious that tell you that something just doesn't feel real.

On Non-White Light

The biggest incongruity between photographic light and light in the real world often comes down to color. Our flashes are white, right out of the box. But real light is not like that. This disconnect often leads to light that is too sterile to be convincing.

Damn, this hits close to home. I literally did exactly that about five years ago.

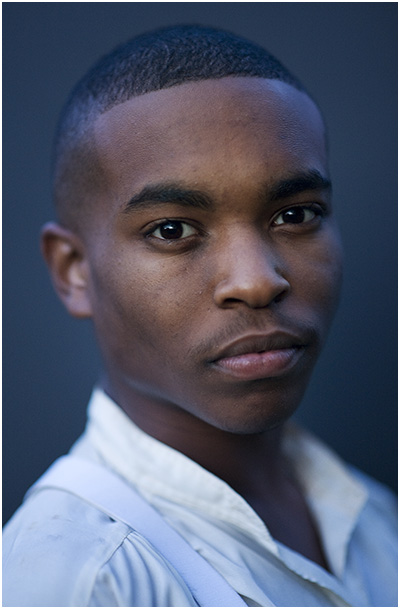

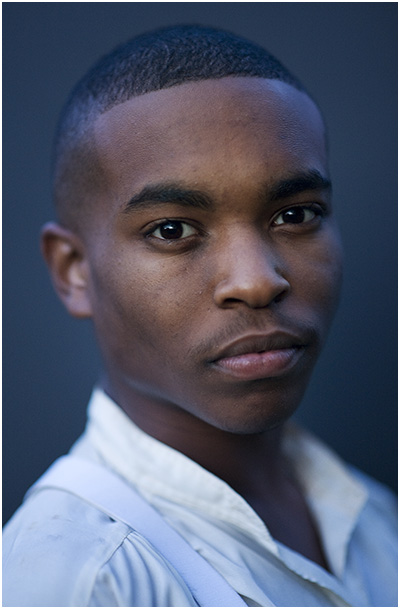

I had been lighting this dancer in motion. Then we did some head shots afterwards. It was last light; his face lit by the deep dusk afterglow, with the encroaching night at his back. I had an assistant hold a black foam core board behind the subject's head.

The foam core removed the background, but it left the light. It wasn't very big, so the blue background light seeped in around the edges. There wasn't very much light, maybe ~1/8 sec at f/1.4 at ISO 1600, or something like that. But the quality...

When I saw the photo I remember thinking, this light is so much more real and organic than what I am producing with my flashes. This is what the real world is like, and it is so much better than my sterile-lit photos.

On the Basic Building Blocks of Gels

[Morpheus voice] What if I were to tell you that it could all come down to one gel? [/Morpheus]

I'm kinda kidding, but not really. It is easy to get overwhelmed by the sheer number of colors in play when it comes to gels. But in reality it is much more simple than that.

Okay, I’m guessing not everyone fully got what Greg just dropped. What he is talking about is a cool way of distilling that the color of light is mostly about the warm-cool spectrum, and and that it also comes down to your point of reference.

Let’s unpack this a little.

Say that you have, oh, five speedlights and a nice-sized chunk of half CTO gel. You are interested in working with the full warm-cool spectrum, spanning from a full shift to CTB blue and ranging all the way to full-shift CTO orange.

If you set your camera’s white balance to tungsten, your ungelled flash (#1) will be recorded as a full CTB shift—AKA blue.

Add a half CTO gel to flash #2, and—in tungsten white balance—and it will be recorded as looking like a half CTB blue. (Remember, ungelled, it is all the way blue. You are warming it by a half CTO, taking it halfway from blue to to white. Which is equal to a half CTB if you were in daylight balance.

Add two layers of half CTO (which equals a full-cut CTO) to flash #3, and you have brought it completely from blue to white.

Add three layers of half CTO (AKA one and a half CTO) to flash #4, and it will net out as half CTO in a tungsten white balance environment.

Add four layers of half CTO (AKA a double-cut CTO) to flash #5, and it will render as full CTO in a tungsten white balance environment.

Is that cool (and warm) or what? One gel yields a full spectrum of warm light to cool. It is all about the relative perspective of your white balance setting, and how much you shift from there.

It's just a trick to make a point. Much of lighting is about understanding tha nature of the warm-to-cool spectrum, and bumping various lights in the direction that you need them to me.

On Cooling and “Dirtying Up” the Fill light in the Shadows

Note: The photo referenced below is from the Michael R. Bloomberg spread on pages 156-157 in 50 Portraits.

A couple of things, for clarity.

First, a "plusgreen" is a pale-ish green fluorescent gel that would turn the light from your flash into the green of a traditional, old-time fluorescent lamp.

Plusgreens are also referred to as "window greens." Because if you thusly gelled the entire window area in a room, then the incoming daylight would match overhead fluorescent lights. Then you would correct it all at the camera with a complementary magenta filter or white balance setting.

Second, the key light on Bloomberg photo is gelled with a half CTO. The fill light is a mix of CTB and plusgreen. There is no white light in this frame. But it looks so natural—maybe even better than natural. Look closely at his face. Look at his hand. The light doesn't look clinical. It looks painterly.

This is the heart of understanding color, in a single photo.

On CalColor®, Before it Existed…

Rosco CalColor®, as you know, is a full set of calibrated gels in primary and secondary colors. The flip side of that measuring scale is a color meter, which measures the filter-pack-calibrated color of actual light.

Basically, every color of light can be numerically reproduced. And Greg wanted a quantifiable understanding of the various color components involved.

Where we might notice that light looks different at different times of day and/or in different environments, Greg dove deeper. He approached it almost like a scientist. And what his data and experience told him was that it was mostly all about a small family of colors.

So yeah, Rosco CalColor® gels can give you whatever color that you want. But in the end, you'll probably live in a pretty small neighborhood of chosen color components.

On the Lighting Hues that Create an Environment

For photographic light to look "normal," yet still capture the complexity of the real light in the world around us, you need to progress from white (or even a straight, warmer white) to using a combination of colors. But the magnitude of those color shifts need not be very great.

Note: The photo Greg is referencing here is on page 202 of 50 Portraits.

No, no... this is white light. Right? Right?

But it looks... wait... yeah, those hues in the shadows. I see it now. And look at the specular highlights on Springsteen's shoes. They're... blue. Because they see the upper light that Greg gelled with the half CTB. (The lower, second soft box was gelled with a half CTO.)

Here's the thing. We don't see this consciously—even as light-conscious photographers. Hell, I often don't see it consciously even as a photographer writing a freaking lighting blog.

But our brains soak it in. Our subconscious sees it. And without reporting why, our brains just register chromatically complex light as more real.

Conscious, thinking-photographer brain, meet subconscious lizard brain photographer. Maybe you two should talk.

The Best Way to learn this

So how to we get from Point A to Point Greg?

You can read about it until you are blue in the face. But there is only one way to really learn it.

And to be sure, some of you may be counting yourselves among the latter, which is fine.

Not me. This is some OMG IT'S FULL OF STARS shit to me. This is the magic in pictures that most viewers will not even consciously perceive, yet all will subconsciously absorb as a layer of realism. This is magic we can create as lighting photographers.

This is getting fun.

NEXT: Greg's Assignment

Today’s Lighting 103 post features excerpts from a bar conversation with Greg Heisler. It's just as if we cornered him at a conference (which I did) and he agreed to have a drink and talk color (which he did).

This is roadmap stuff. It's above and beyond the specific info he includes with each of the assignments in his book, 50 Portraits, the companion text to L103.

__________

Here's the scene. It's a few minutes after midnight at an Embassy Suites near the airport in Columbus, Ohio. Greg and I grab a drink just as the bartender is closing her register in the lobby bar.

I have had a few of these types of conversations with Greg, for which I am grateful. He is always so generous with his knowledge and experience, as those of you who have read his book can attest.

We talked for a couple hours—an early exit by past standards at the Vista bar in Dubai. I was recording, with permission, so I could avoid spending the time scribbling. Below I have transcribed the half-dozen or so takeaway nuggets that I would have been wracking my brain to remember the next morning.

It's tough, because it's the side stories woven throughout, and not the nuggets, that you tend to remember. So we'll be sticking to the salient takeaways. And not, for instance, relaying the parable about the photographer who finds success shooting nothing but hairy rectums with a red gel.

(Moral: Your work will never make everyone happy. But if you're lucky, it'll make some people really happy.)

And for the record, that vignette would not even crack the Top Ten of photo-related stories that came out of late night talks at The Vista in Dubai. (And I'm pretty sure David Burnett holds positions one through five.)

For clarity, the text with inset borders (AKA blockquotes) is Greg talking.

Why are Color and Light so Important?

Light is its own environment. Just as we can drop a subject into a physical environment, the color and quality of the light is an environment unto itself. It can create an imaginary environment, with elements unseen in the frame yet obviously influencing the subject.

As Greg puts it:

"Color and light is a narrative code. Basically, everybody everywhere all over the world gets it. If you’re a storyteller, you can tell a story with light in a way that everybody will understand beyond words.

And that’s powerful. Because it feels the same to everybody. Recognizing light as a storytelling tool is a big thing."

Translation: the universal nature of light and color can make a photo instantly appear as organic and authentic. Or it can set off warning bells in your subconscious that tell you that something just doesn't feel real.

On Non-White Light

The biggest incongruity between photographic light and light in the real world often comes down to color. Our flashes are white, right out of the box. But real light is not like that. This disconnect often leads to light that is too sterile to be convincing.

"The imperfectness of it [light] is what’s good. And I think what’s boring about photography and color when you’re doing portraits, is that people are just like, pink or brown or whatever they are. And it’s just, like, [whacks the table] a thing.

And in paintings, that’s never the case. In paintings you can see blue veins and there’s all these other colors in there. So I felt like, when I would do portraits of people in white light or warm light or whatever, it was always just mono… not monochromatic, but just a literal kind of color.

And that was always just unsatisfying to me. So what I wanted to do was try to create that light where the color had a depth to it, and other sources were not seen but implied.

Like there’s lighting coming from someplace else. We don’t know what it is, or where it is. But there’s this richness that actually makes it seem like a real moment; a real-life environment.

Even though it feels like it’s in a studio, the quality of the light is so much richer and more complex, it couldn’t be in a studio. It’s almost like you dropped a black background … somewhere."

Damn, this hits close to home. I literally did exactly that about five years ago.

I had been lighting this dancer in motion. Then we did some head shots afterwards. It was last light; his face lit by the deep dusk afterglow, with the encroaching night at his back. I had an assistant hold a black foam core board behind the subject's head.

The foam core removed the background, but it left the light. It wasn't very big, so the blue background light seeped in around the edges. There wasn't very much light, maybe ~1/8 sec at f/1.4 at ISO 1600, or something like that. But the quality...

When I saw the photo I remember thinking, this light is so much more real and organic than what I am producing with my flashes. This is what the real world is like, and it is so much better than my sterile-lit photos.

On the Basic Building Blocks of Gels

[Morpheus voice] What if I were to tell you that it could all come down to one gel? [/Morpheus]

I'm kinda kidding, but not really. It is easy to get overwhelmed by the sheer number of colors in play when it comes to gels. But in reality it is much more simple than that.

"Like, there are a million colors out there. But we could look around this room, and everything you see is either warm or cool. Like 99% of everything you see is either warm or cool.__________

And the truth is, you could have a full and happy career with just a half CTO. Because you could double it up, or quadruple it up, and then you could move your white balance, and decide where you wanted it to be. So you could do everything with that."

Okay, I’m guessing not everyone fully got what Greg just dropped. What he is talking about is a cool way of distilling that the color of light is mostly about the warm-cool spectrum, and and that it also comes down to your point of reference.

Let’s unpack this a little.

Say that you have, oh, five speedlights and a nice-sized chunk of half CTO gel. You are interested in working with the full warm-cool spectrum, spanning from a full shift to CTB blue and ranging all the way to full-shift CTO orange.

If you set your camera’s white balance to tungsten, your ungelled flash (#1) will be recorded as a full CTB shift—AKA blue.

Add a half CTO gel to flash #2, and—in tungsten white balance—and it will be recorded as looking like a half CTB blue. (Remember, ungelled, it is all the way blue. You are warming it by a half CTO, taking it halfway from blue to to white. Which is equal to a half CTB if you were in daylight balance.

Add two layers of half CTO (which equals a full-cut CTO) to flash #3, and you have brought it completely from blue to white.

Add three layers of half CTO (AKA one and a half CTO) to flash #4, and it will net out as half CTO in a tungsten white balance environment.

Add four layers of half CTO (AKA a double-cut CTO) to flash #5, and it will render as full CTO in a tungsten white balance environment.

Is that cool (and warm) or what? One gel yields a full spectrum of warm light to cool. It is all about the relative perspective of your white balance setting, and how much you shift from there.

It's just a trick to make a point. Much of lighting is about understanding tha nature of the warm-to-cool spectrum, and bumping various lights in the direction that you need them to me.

On Cooling and “Dirtying Up” the Fill light in the Shadows

Note: The photo referenced below is from the Michael R. Bloomberg spread on pages 156-157 in 50 Portraits.

"What I often times would do, like for the portrait of Michael Bloomberg—it’s a thing I started doing that I really like—is let’s say I used [in the shadows] a CTB. I would also use a "plusgreen." The plusgreen would dirty up the CTB. Because the CTB on white people makes them look like poached fish. It’s kind of slightly purple, on pink skin. It just looks funny.

The plusgreen keeps it looking more blue. I might do, like for the Bloomberg thing, I might put a full plus green on a CTB, or a 1/2 or 3/4 plusgreen on a full CTB. And what that would do is exactly what you are looking at, which is around this [camera right] side. It kind of moves into a slightly green cast."

A couple of things, for clarity.

First, a "plusgreen" is a pale-ish green fluorescent gel that would turn the light from your flash into the green of a traditional, old-time fluorescent lamp.

Plusgreens are also referred to as "window greens." Because if you thusly gelled the entire window area in a room, then the incoming daylight would match overhead fluorescent lights. Then you would correct it all at the camera with a complementary magenta filter or white balance setting.

Second, the key light on Bloomberg photo is gelled with a half CTO. The fill light is a mix of CTB and plusgreen. There is no white light in this frame. But it looks so natural—maybe even better than natural. Look closely at his face. Look at his hand. The light doesn't look clinical. It looks painterly.

This is the heart of understanding color, in a single photo.

On CalColor®, Before it Existed…

Rosco CalColor®, as you know, is a full set of calibrated gels in primary and secondary colors. The flip side of that measuring scale is a color meter, which measures the filter-pack-calibrated color of actual light.

"Like, decades ago, I had this idea that what I wanted to do was to work with color. So I got a color meter. And every time I saw a kind of light that I liked, I would measure it. And then find the gels that were that color.

So if what I wanted was 5:30 in the afternoon on Oct 22 under the Brooklyn Bridge, like, [click] oh, it’s this one. And I would just do that in a very subjective way.

And ultimately I think that there are, like, just six colors and you just recombine them and use them again and again. I don’t think it is really that complex."

Basically, every color of light can be numerically reproduced. And Greg wanted a quantifiable understanding of the various color components involved.

Where we might notice that light looks different at different times of day and/or in different environments, Greg dove deeper. He approached it almost like a scientist. And what his data and experience told him was that it was mostly all about a small family of colors.

So yeah, Rosco CalColor® gels can give you whatever color that you want. But in the end, you'll probably live in a pretty small neighborhood of chosen color components.

On the Lighting Hues that Create an Environment

For photographic light to look "normal," yet still capture the complexity of the real light in the world around us, you need to progress from white (or even a straight, warmer white) to using a combination of colors. But the magnitude of those color shifts need not be very great.

Note: The photo Greg is referencing here is on page 202 of 50 Portraits.

"It’s more like it’s all fractional stuff [as opposed to full-strength CTOs and CTBs]. Even if it’s white light, even if it’s a situation that doesn’t have colors, it would have color. Like there’s one I have of Springsteen and he’s standing by a window. And basically, it is supposed to look like he is standing by a window. Except for it’s all lit.

And there are a couple of soft boxes outside, except the one from above had some blue and the one from below had some warm. Like light bouncing off of pavement.

So he’s getting a couple of soft boxes from outside. On the wall behind him, there’d be the shadow of his head. But the shadow is bluer [as if being filled by the sky]. And it’s that kind of stuff that makes it feel like a real environment to me.

It would be a perfectly fine picture if it just had an Octabank outside the window. It would look nice, for sure. But it wouldn’t be as chromatically complex. And I think that’s what’s neat about it. And, look, I just get my rocks off with it because I think that’s neat and I that looks like what you see.

I try to make it look like what I think I see. And photographs always look too sanitized. They never look like what I see."

No, no... this is white light. Right? Right?

But it looks... wait... yeah, those hues in the shadows. I see it now. And look at the specular highlights on Springsteen's shoes. They're... blue. Because they see the upper light that Greg gelled with the half CTB. (The lower, second soft box was gelled with a half CTO.)

Here's the thing. We don't see this consciously—even as light-conscious photographers. Hell, I often don't see it consciously even as a photographer writing a freaking lighting blog.

But our brains soak it in. Our subconscious sees it. And without reporting why, our brains just register chromatically complex light as more real.

Conscious, thinking-photographer brain, meet subconscious lizard brain photographer. Maybe you two should talk.

The Best Way to learn this

So how to we get from Point A to Point Greg?

You can read about it until you are blue in the face. But there is only one way to really learn it.

"I think what you have to do to be able to see it, is to shoot it. And then shoot it.

Like, shoot it the clean way, with white light. Then the next way is to shoot it with a warm and a cool. And so you see that. And then muddy up the light a little bit, and then see it that way.

And I think some people would look at it and go, “Well, yeah, I guess…” And that’s fine. To me it’s a big deal. But I don’t necessarily think it would be a big deal to everybody. Like, I think some people wouldn’t even like it probably."

And to be sure, some of you may be counting yourselves among the latter, which is fine.

Not me. This is some OMG IT'S FULL OF STARS shit to me. This is the magic in pictures that most viewers will not even consciously perceive, yet all will subconsciously absorb as a layer of realism. This is magic we can create as lighting photographers.

This is getting fun.

NEXT: Greg's Assignment

__________

New to Strobist? Start here | Or jump right to Lighting 101

My new book: The Traveling Photograher's Manifesto

Permalink

<< Home